The latest in director Soi Cheang’s saga inspired by the classic novel Journey to the West might be the strangest one yet. The franchise blockbuster has always been a weird fit for the former director of indie horror movies and slick crime dramas, and Cheang’s first Monkey King was kind of a mess, taking place in an almost parodically artificial computer-generated environment when it wasn’t populated by humans in sub-Cats animal costumes, and led by a distractingly fidgety performance by an unrecognizable Donnie Yen. The second film was a big improvement, as the effects were higher quality and more strikingly original, the acting, with Aaron Kwok taking over the title role and Gong Li playing the primary villain, much improved and the story much more in Cheang’s comfort zone. The second one was the first to follow the Journey to the West itself, with the Monkey King designated to help Xuanzang, a Buddhist monk from Tang Dynasty China, travel to India in order to bring back essential scriptures. The plot involves the Tang monk’s efforts to reform the White-Bone Demon (Li), a malevolent creature whom everyone else would prefer to simply destroy. The Monkey King must learn to submit his violent impulses to his master’s compassion, despite his firm belief that he knows best.

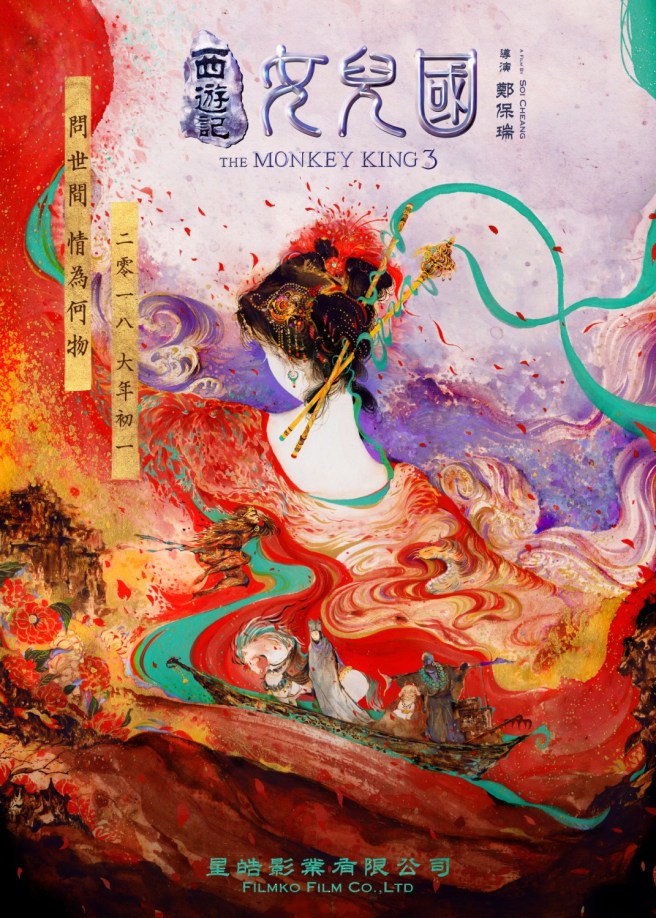

The third film in the series opens with an image from the second, the massive skeletal incarnation of the White-Bone Demon glowering over the Earth, and flips it, literally, as we plunge into a film wholly opposite its predecessor. Where the second film was dominated by mountain snow, dark nights, and cruel, demonic violence, this one takes place in lush green riverlands, and its concerns will be romantic and all-too human. Escaping an angry river god in the film’s first moments, the monk and his party (the Monkey King, the reformed pig demon Bajie, the blue-skinned muscle-man Sha, and their magical White Dragon Horse) are thrown, thanks to a wormhole helpfully provided by Buddha himself, into a secluded kingdom populated entirely by women. Men are banned from the kingdom, and the heroes are to be executed on sight but are saved by the young queen (Zanilla Zhao, an earnest waif last seen here in Duckweed), who has fallen in love with the monk. With a few sidetracks (including an ill-considered subplot about obtaining abortions for the men who become pregnant and some spectacular water effects as the river god reveals his own unrequited love story), the rest of the film is about Xuanzang’s desire to remain with the woman he now loves and his need to abandon her to continue his quest.

This is one of the more interesting aspects of the monk’s story, and he really takes center stage here, with the Monkey King relegated to a supporting role. William Feng builds on his strong work in the second film with his most soulful performance yet. The Kingdom of Women story in the novel plays out very differently, with the monk pretending to marry the Queen and then sneaking away, and it’s not one I’ve ever seen adapted before. Though Stephen Chow’s Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons has the monk come to the same realization, that you can’t really renounce anything if you don’t have any attachments in the first place, as the final step in his enlightenment. Choosing this as the next story in the saga I think is a telling choice, especially when one might have expected a more famous subject like the Cave of the Spider Women, in which female demons lure the heroes with the promise of sex and then try to eat them. That would have been more in line with the White-Bone Demon story of the second film. But instead Cheang zigzags into completely the opposite type of story, neatly subverting the misogyny inherent in both the original Kingdom of Women chapter and the popular Spider-Women stories. Once again, Soi Cheang has utterly defied expectations within a single blockbuster film series: from goofy cartoon to bleak action horror to gorgeous romantic tragedy.